My dad was 91 years old when he watched the two part documentary Jimmy Savile: A British Horror Story. He was painfully perplexed by the end of it. It really was beyond his comprehension. We talked about it. He could not understand both the monstrosity of the sexual violence or how Savile was able to get away with it for so long. After all, here was a friend of the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, someone who was close to the future king of England, and had his own set of keys to Broadmoor hospital. Someone like that is undoubtedly scrupulously investigated by the intelligence services who must surely known of the serial abuse.

My dad always remained interested in the world and towards the end he found out more and more that disturbed him. In his late eighties, he stopped reading the Daily Telegraph, having been disappointed in it for many years, and moved to The Guardian. On day one, he read an interview with Hannah Gadsby and was fascinated by what she said,. Reading the work of George Monbiot, he found a perspective that was almost entirely ignored by the rest of the mainstream press.

He read widely.

He had a biography of Lord Mountbatten, another person close to both the future king and the Duke of Edinburgh, but it had no mention of the lord’s penchant for teenage boys, even though this was known for decades and there was a big FBI file; close to power and untouchable.

My dad had a couple of Laurens Van Der Post books on the people of the Kalahari, but again, knew nothing of Van Der Post abusing a 14 year old girl who was meant to be escorting to England. He was 46 years old. She became pregnant and he abandoned her. Van Der Post was a spiritual guru to the future king.

These stories are not even hiding in plain sight. They are being found and then passed fit for power.

One of the reasons my dad retired as soon as he could was because he saw that the idea of “my word is my bond” existed less and less.

He believed a promise was a promise.

Perhaps the greatest example of this was when my mother’s mental illness was at its worst and she was close to being sectioned. The doctor advised him that it would be best to put her in a residential home and get on with the rest of his life. This was a firm “no”. He had promised “in sickness and in health” and his word was his word.

(my mother was remarkably strong in fighting he battle too)

After he died, my eldest niece told me a story he had never shared with me.

He idolised his father, a man I never knew. One day, when he was a little boy, they were walking through woodland and came across a poacher.

“Evening, sir”

“Evening, sir”

Afterwards, my dad said, “why did you call him ‘sir’, he’s a poacher”.

My grandfather corrected him, “he is another human being”.

That lesson stuck.

When my niece went to volunteer for Maytree Respite Centre which does remarkable work to help suicidal people, he was fascinated. Suicide was something that had never crossed his mind. He wanted to know how other people came to the conclusion that it was a necessary possibility.

I write all this because I am reading Lucia Osborne-Crowley’s The Lasting Harm, the story of Ghislaine Maxwell’s trial, but in particular, the story of the victims who took to the stand. Lucia has also been a a victim of rape and child abuse. She got up at 1.30am every morning to ensure she would be among the first four journalists who were admitted to the trail.

To sit through so many tales of power and sexual abuse when you have been the victim of power and sexual abuse takes an incredible amount of courage and tenacity. My late friend Barry Crimmins was raped when he was four. He became a great comedian and activist, always fighting for the bullied.

When he discovered AOL had a multitude of corners where people shared images of sexual violence towards children, he fought very hard to be heard. He was often either ignored or brushed aside with weasel words.

This battle, the toll on his mental health as he collated an enormous body of evidence and, in doing so, had to relive his own violent experiences, eventually led to a hearing in Washington. (I recommend that you watch Barry’s story - Call Me Lucky).

I am thinking about him too as I read Lucia’s book.

I find myself frequently grimacing and having to put the book down.

I feel like my father must have felt as he watched A British Horror Story, but I know I must keep reading. Apparently, the FBI knew about Epstein for thirty years. Another man mixing with Presidents, politicians and the powerful.

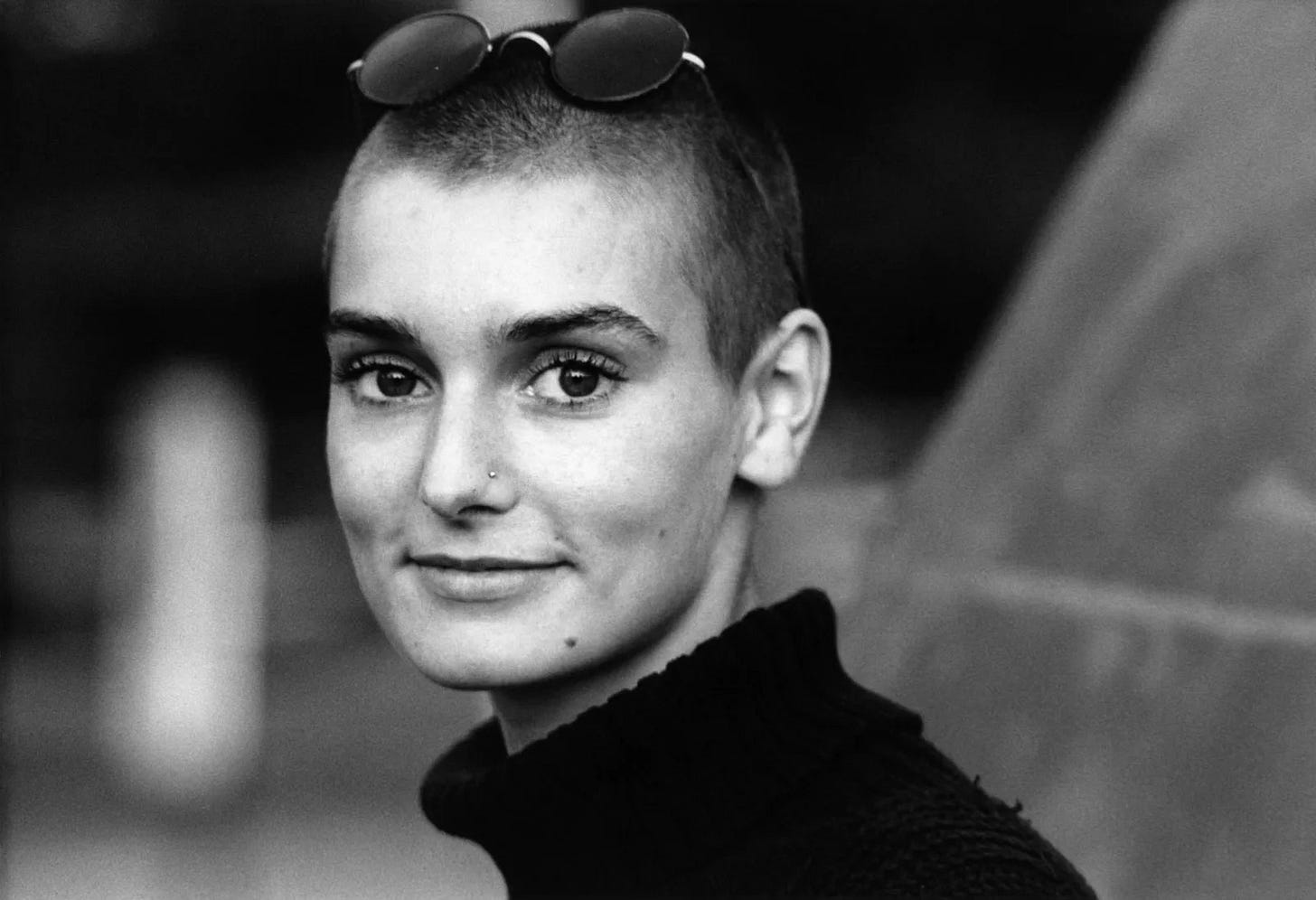

I also think of Sinead O Connor, another hero of mine.

How she stood up and spoke out and for that was cast out as a madwoman, derided and demeaned.

I think of Viktor Frankl. The psychotherapist who was imprisoned in Dachau concentration camp. He returned to Vienna when he was freed. He spoke of meeting many people who were filled with apologies, “I am so sorry, Viktor, we knew nothing of what was going on”. He considered this to be true, but added that he believed they had had to work hard to make sure they did not know what was going on.

The whistleblower is rarely lauded and often cast out.

In the last few months of his life, I think my dad had had enough.

He looked at the duplicitous, greedy, and careless politicians who didn’t even have to hide much of the worst of their nature.

He looked at how much the media failed to represent and how many stories didn’t make the pages.

He was no great admirer of Mohammed Al-Fayed and would not have been shocked by the revelations. Though as we know, these are not revelations, these were known knowns.

I worked at Harrods toy department in my late teens.

One of my friends who was fortunately, very wary, soon found out how the system worked. One of the department managers would say that Mr Al-Fayed wanted to see what the new toys were and the manager would go with her to show the latest in the ranges. The manager would then make their apologies as they “must get back on the floor” and leave the young woman with Al-Fayed.

It was just the way things were.

In many places, I imagine it is probably still the way things are.

This is why The Lasting Harm is important.

It reminds us to be alert, to listen, to be ready to support, to intervene, to be stronger.

On the anniversary of Sinead O Connor’s death, I wrote this poem.

Is it an ugly envy that drives us to crush

those who wish to expose us to the possibility of beauty

And the hope of change

To unbalance the power and oppression of the world

At your peak on a platform

prepared to propel you to platinum

Instead

You dismantled your stage

By daring to tear into a photograph of an abuse concealer

A papal alibi for paedophiles

your failure to obey the rules of silence outraged.

Not anger at the perpetrators or the pope

it was you that betrayed the sacred trust

She must be mad

She must be kicked

she must be silent

the media soon don the garb of Vatican emissary

a reminder of their deference

that considers calling out the true offence

History shows that most oppressors

will have eager dressers

to clothe them in camouflage

you never complimented the emperor on his hosiery

cast out , a not for profit prophet

In the desert something grows

it blunts chainsaws when it blossoms

And it can't be felled

and on its leaves grow the stories

that they still battle to conceal.

Power inequality exists in so many places, including someone's own family. I deeply admire people who stick their head over the parapet, even knowing the fusillade it will bring down on them.

I grew up in Ireland and I was very young when Sinead tore up the picture of the Pope so i didn't really understand what was happening but I knew Sinead was telling us something important. I am so very glad I came across your Substack (I found it through Stewart Lee). Thank you for writing.